Howgill Fells: A massif hiding in plain sight

Imagine a statuesque range of voluptuous hump-backed hills, cloaked in green velvet and rippled by an amplitude of homogeneous ridges sweeping gracefully down to a petticoat of bucolic pastures. Move in closer and a contrast emerges, for the ridges are separated by deeply riven gills, spouting lively streams that give vigour to an otherwise tranquil scene.

With the coming first of a railway and then of a motorway, the Howgill Fells were brought forward from imagination and obscurity for all to see. Today’s traveller cannot fail to be impressed by their sleek uniformity of appearance, yet this has resulted in only a marginal increase in popularity, because the viewer’s thoughts soon resettle upon the illustrious heights of the neighbouring Lake District. As such, if a list were compiled of Britain’s most overlooked hills, the Howgills would be amongst the most unjustly dishonoured.

Geologically, this discrete upland block belongs to the southern Lake District, being a component of the ‘Windermere Supergroup’ (a grandiose title that must surely have also been adopted by a band of local musicians). The rocks are Silurian sandstones and slates, some one hundred million years older than the Carboniferous limestones of the adjacent Yorkshire Dales, from which they are separated by the extensive Dent Fault.

Geographically, matters are even more bewildering. The Yorkshire Dales and Howgills both belong to the Yorkshire Dales National Park although, like the Lake District, the Howgills are part of Cumbria. Nevertheless, the southern half of the fells used to identify as Yorkshire. Indeed, this same portion was within the Dales National Park, until an extension to both parks in 2017 absorbed the rest and brought the Lake District eastwards to abut the new boundary; the two national parks separated at their closest point merely by the six lanes of the M6 Motorway.

The Lune Gorge marks the western perimeter of this heart-shaped massif, with the deep valley of the River Rawthey to the east, itself a tributary of the Lune. To the north, the Lune curves around to its source on Green Bell, the highest of the north-eastern summits, which appropriately is a watershed mountain, supplying both the Lune and the Rawthey, but also draining into the River Eden that heads north to the Solway Firth.

To the south, beautifully situated at the apex of the heart lies the only settlement of any size, Sedbergh, a historic small town, where the principal employment was formerly home knitting, in common with much of what was the West Riding of Yorkshire. In more recent years Sedbergh has become England’s official ‘Book Town’ and has also joined the ‘Walkers are Welcome’ scheme.

Sedbergh (the “gh” is silent) is the most common starting point for walks on the Howgills, with the highest summit, The Calf, being customarily climbed from here as an out-and-back excursion. However, there are around thirty named tops in these fells and choosing the catchment area for our Worthy is necessarily arbitrary. The Calf itself is hardly distinguishable from adjacent summits, and barely taller, so its top must simply be considered as the high point of a central, collective dome with radiating ridges, each broad tendril contributing to the whole. This Worthy could be described as “The Calf Family”.

Click on the map below to move around. The scale can also be altered by zooming in and out.

Let us, therefore, examine the wide variety of ascent routes that contrive to converge upon The Calf. As Sedbergh is the most popular, this is where we will begin on what might be considered as the tourist route, following Settlebeck Gill to reach the ridge. The alternative via Lockbank Farm, which slants across Winder is less used although is blessed with more open views.

The main route has been adopted as part of the Dales High Way, recognised as a Long Distance Footpath in 2014 and added to OS maps of the region. As part of its ninety-mile length, the path traverses the Howgills along its major north-south ridge between the relative bustle of Sedbergh and the deep quiet of Bowderdale, a walk of around nine miles. For those with two cars at their disposal, this affords a splendid high-level outing taking in the fundamental substance of the Howgill Fells. The use of public transport is mostly a non-starter, other than to reach Sedbergh as a base.

Leaving Sedbergh’s narrow streets, the initial slopes climb across the flanks of the town’s personal hill, Winder, a delightful height that should be incorporated into your walk. If returning to Sedbergh, it provides a lovely conclusion and final viewing point, with both a trig pillar and a topograph, erected by the townsfolk in 2000. Incidentally, Winder is spoken with a short ‘i’ in the manner Alfred Wainwright observed “as Eliza Doolittle would have pronounced ‘window’ pre-Higgins”.

Wainwright published what is still the authoritative guide to the Howgills, most later books merely incorporating the massif as a subsidiary to other areas, presumably in the hope of boosting sales (even AW added a few extras to fill his volume). This underlines the backwater nature of these fells. Wainwright’s guide was published in 1972, then revised in 2014 and, as there is little change in these hills, it stands good today.

There are usually a few people on Winder, if only local dog walkers, and you will likely encounter hillwalkers on the path to the Calf. This is as popular as the Howgills get, so don’t be deceived. Take most other routes of ascent, and you will be alone until reaching the summit.

The main path avoids the summit of Arant Haw, although it saves little in distance or altitude. The views from the top are better, so do include it.

Up here, there are no walls and few fences to impede progress. For this reason, the Howgills have long been regarded as some of the finest ski mountaineering country in the north. There are drystone walls at lower levels, generally around the 300m contour, that enclose the intake land, leaving the higher ground as shared common grazing land.

The Howgills are home to a lesser-known native breed of sheep known as the Rough Fell; hefty, docile and exceptionally hardy they are farmed almost exclusively in these fells and those of South Cumbria. Their appearance is similar to that of Swaledales, who also roam these hills, but Rough Fells exhibit just a white nose band and no white around the eyes (pictured left).

Also native are semi-feral fell ponies that wander the Howgills, the herds managed by just a small number of breeders.

On this ‘tourist route’ the path is obvious throughout and easy to follow. Some apparently arbitrary sections have been surfaced with a gravel track, which creates a jarring scar disrupting the silky, verdant ridgeline. As well as walkers, the rolling nature of these fells is a prize draw for mountain bikers, and this route is regarded as one of the finest MTB routes in Britain. The main path is classed as a bridleway so is legal for cycles to use and, being a bridleway, and not a path laid out for walkers, is the reason why the main path does not always visit the actual hill summits. Curiously, on the very top of The Calf the map indicates that the bridleway briefly disappears, so if you see any cyclist there, pedantically remind them to carry their bikes over that bit!

Much of the route from Calders to The Calf is a gravel track, although you must briefly wander across no man’s land to attain Bram Rigg Top. Few people do, as it is easily overlooked when being traversed. It’s almost imperceptible, featureless and, as the name suggests, is merely the top of Bram Rigg, the long ridge descending to the west.

Regaining the track, there is a short descent to a pronounced col, where the path from Cautley Spout attains the ridge. Together, it’s merely a short step to the summit of The Calf. Most of the summits muster a small cairn despite the lack of available stones on the grassy tops, however, The Calf does not need one, as it boasts an OS trig pillar. A surprising sight, just north-east of the summit, is a shallow tarn that does occasionally dry up in the summer. The tarn can easily be missed by those approaching from Sedbergh.

The height and central location combine to construct a view that grabs attention. As Wainwright declared, “there is not a more extensive panorama in England than this”. The Lakeland Fells from Blencathra to Black Combe are laid out in splendour and the Pennines sweep around the entire eastern half of the compass from Ingleborough, almost due south, to Cross Fell approaching the northern arrow. Everything appears distant; even close fell tops look disconnected, as though we occupy a position unshackled from the world at large.

Does it strike you as peculiar that the highest mountain in a range is called The Calf? The conventional assignment of such a name would be to a smaller hill of a parent, which in this case is clearly inaccurate. The name Calf first appeared on Greenwood’s Large Scale Map of Yorkshire in 1817; previous to that, Thomas Jeffreys’ rustic 1771 map records what may have been a colloquial name to imply the typical conditions on top – “Cold Arse” (!) The name of Calders is likely to have derived from this (in fact Jeffrey’s 1770 map actually labelled Cold Arse as the summit of Calders and not The Calf, perhaps in error, which may explain why the map was reprinted the following year).

Naturally, the first maps of the Ordnance Survey adopted the less controversial title but did not apply any name to either Calders or Bram Rigg Top. By the 1890s the OS had named them but did not assign spot heights, which led to some speculation regarding which was highest. At 2220ft (676m) The Calf claimed the crown, but it was not until surveys a century later that the OS confirmed Calders as just two metres lower at 674m, with Bram Rigg Top at 672m.

The second most popular ascent of The Calf commences from the Cross Keys Inn at Cautley on the River Rawthey. This is partly because it is the shortest walk, although is mostly due to this route being the most dramatic. After all, there are crags and waterfalls!

The Howgills were heavily glaciated, although there are few of the normally associated features such as mountain corries. Cautley Crag is the one exception, sporting a mile-long precipice bounded by England’s highest combined waterfall cataract – the 650ft (198m) Cautley Spout.

Before crossing the river at the start of the walk, the Cross Keys itself warrants some attention. It looks like a traditional country pub and was at one time, although it has for many years been a temperance hotel. Originally a farm, later converted to an inn, the story goes that the landlord lost his life falling into the river while assisting a local home one night. The subsequent owners dispensed with the liquor licence and, in 1949, gave the building to the National Trust. The present tenants run it as a B&B and café, the specialities of the house being herbal cordials. Nonetheless, you can take your own alcohol and they provide glasses for free. It’s a charming place, more like a home than a hotel.

Crossing the bridge, we follow Cautley Home Beck towards the falls. To the right is the relatively solitary hill of Yarlside, worth a climb up its long ridge above Ben End, which as it levels off, affords the finest grandstand views of the spout waterfalls. Otherwise, the valley route leads gently up to the foot of the gorge.

A well-constructed path climbs the right bank, curving round above the lower falls to contemplate the upper ones. The highest individual fall is around one hundred feet. During hard winters, the falls freeze to form what is often regarded as England’s finest frozen waterfall climb, due to its cascading nature and extensive length. I climbed it in favourably frozen condition in 1986, although sadly took no photographs, so consider that opposite (or above on a mobile) as representative!

Above the falls is a shallow valley. A direct, pathless assault on the summit can be undertaken from here with no difficulty, although most continue alongside the Red Gill Beck to the col. By the stream is a stone washfold, a sheepfold used in olden days by shepherds dipping their flock in the beck. It had become derelict but was rebuilt in 2002 by Andy Goldsworthy as part of his expansive sheepfold art project for Cumbria County Council. This example was inspired by the Foot and Mouth epidemic. The addition to the original fold is a pointed cairn at one outside corner, representing forced exclusion from the land, and a deliberate gap within the cairn represents the loss of time.

An alternative, circuitous ascent from here to The Calf clings more closely to the edge of Cautley Crag, firstly reaching the summit of Great Dummacks, although the flat ground hereabouts is too vague to afford a definitive top. The high point is of no consequence. Instead, continue a short distance down the ridge, dropping to the left around the crag. Here you will discover the finest prospect of Cautley Crags. Undeniably, they are steep and impressive to gaze upon, yet the face is broken and the rock is too friable to contemplate closer inspection. The Howgills are no place for rock climbers.

From Great Dummacks, Calders can be reached easily and thence to The Calf.

Despite the approach from the west being the most commonly viewed, courtesy of the motorway, it is the least employed by walkers. Importantly, the western quarters are the place after which the fells are named. Howgill is a hamlet, along with a collection of farmsteads (at the centre height in the above photograph). Returning to our 1771 map, it was called Hougill, which had been updated to Howgill by the 1817 map. ‘How’ is thought to mean hill, not referring to the hills towering above the hamlet, but to distinguish this settlement’s location above its neighbour Lowgill, lower down by the River Lune.

Thus, for centuries these fells were locally known as the Howgills, although the OS did not adopt this name for the range until after Wainwright had popularised the area in his guidebook. Perhaps that was not the defining reason, although Wainwright had also directly brought the fells to the attention of the OS on a matter of some erroneous surveying.

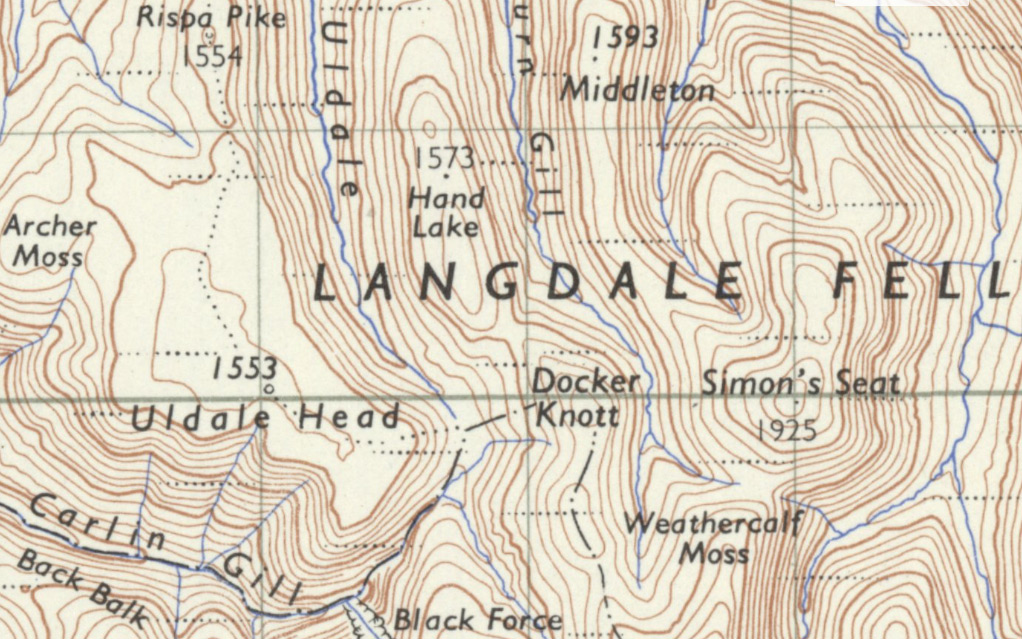

Uldale Head was, since the earliest OS map of the 1840s, afforded a height of 1553ft. AW could plainly see, when judging angles from nearby tops, that this was inaccurate. He wrote to the OS, and they responded by resurveying, subsequently adjusting the height by almost two hundred feet, up to a revised altitude of 1747ft. Basically, the early mapmakers had fluffed the summit contour lines, recording the top as far more of a plateau than it is and subsequent resurveys were less than comprehensive so the error was not corrected.

The southerly fells can be reached by making a circuit from Sedbergh, although there is a very scenic minor lane (Fairmile Road) running under the full length of the western flanks, albeit with challengingly limited parking. Fairmile Gate is the most commodious spot. There are off-road spaces near Carlingill Bridge and the odd considerate opportunity a few hundred yards down the hill from Four Lane Ends towards the Crook of Lune Bridge.

Fairmile Road follows the line of a Roman road that climbed through the Lune Gorge, and for decades I have gazed longingly upon this unfenced ribbon of solitude from the thundering superslab of the M6. Above the lane, the slopes are treeless but thick with bracken, whose colour defines the season. This carpet of ferns is the last to turn green in the spring and the first to turn brown in the late summer. You can see the change of colour filtering through gradually with altitude as each day goes by. It’s a marvel of nature.

The western aspect is the best to immerse oneself amidst the flow of the Howgill ridges, those weighty limbs of the sleeping elephants, many steepening at lower levels, through truncation by the passage of a valley glacier. Between the descending ridges are sharply incised gills, rampant with headwater streams that are inordinately vigorous, tumbling steeply from the high slopes.

Left (above if viewing on a mobile) is Calf Beck, typical of the Howgill streams, where a clutch of active watercourses spring from close to the summit, merge, to be then abruptly slowed into powerful meanders on the valley floor.

With so many waves of ridges, the possibilities for horseshoe walks are myriad and each ridge holds its own secrets. On the subject of horses, few have heard of the mysterious ‘Black Horse of Bush Howe’ and even fewer actually discover it.

The topography of the fells can be confusing, each ridge and slope exhibiting a featureless uniformity that easily leads to misdirection, even in clear weather. However, if you can manage to navigate to the top of White Fell, drop down a short way to the north-west (SD 65930 97412) and look across towards the Heights of Bush Howe (locally pronounced Busha), you will discern an enigmatic arrangement of scree that is certainly not black. However, whether it is natural or created is the question that intrigues. I am definitely in the sculpted by nature camp.

For our considerations of a Howgill Worthy, the main central group of the immediate Calf family would have fulfilled the purpose as a single, unified hill. However, the much lower outlier of Winder is a recommended inclusion, simply for its charm, and so is Fell Head, much higher and closer to The Calf, although comparably little climbed because it inhabits quieter country.

From the west, Fell Head can be combined with The Calf, the connecting ridge capturing the Howgill quintessence of carefree tramping beneath a big sky. All the western arms provide options for descent and, if parked at Fairmile, the intake wall can be followed rather than needing to drop all the way down to the road.

Finally, for a sporting ascent to Fell Head, Carlin Gill offers a unique hands-on experience in the Howgills. Together with the tributary of Black Force (left), these are the most rugged features on the western side. For the most part, a narrow track follows the north bank of Carlin Gill and, when the waterfall of the Spout is confronted, it escapes by an easy scramble up to the left (north). Black Force is also usually avoided on the left, climbing to a fine little grassy arete, although it can be negotiated on its right side. Whilst the majority of the Howgill Fells are open access land, Black Force is a nesting ground and should be avoided from mid-February until the end of May.

“The Calf Family” Worthy – The Calf, Calders, Fell Head, Arant Haw, Winder

Worthy Rating: 75

Aesthetic – 22.5

Complexity – 14

Views – 15

Routes Satisfaction – 15

Special Qualities – 7.5

2 thoughts on “Howgill Fells: A massif hiding in plain sight”

A fascinating and informative article about hills that I love and know well, thanks for posting. Langdale, the valley that cuts deeply into the quieter northern half of the Howgills, is well worth a visit too, difficult to access, largely pathless and utterly remote.

Thank you for your kind comments Richard. I wholeheartedly agree about Langdale, geographically the most complex of all the Howgill valleys and wonderfully wild.