Galtymore: Ireland’s Heartland Height

The Galtee Mountains rise prominently above the lush dairylands of Ireland’s Golden Valley, comprising the highest inland mountain range in the country, with Galtymore representing the sole ‘Munro’ (or Irish Furth) situated any appreciable distance from the coast.

Galtymore is a domineering sight for motorists heading south on the M8 motorway towards Cork, akin to imagining in Britain if Ben Lomond was moved to beside the M1 in Leicestershire. In truth, the Galtees are not the only mountain range in the region, as Ireland’s inland south boasts several distinguished massifs, the Knockmealdown and Comeragh Mountains amongst them, although none approach the lofty heights of Galtymore.

Nonetheless, dominance and altitude may carry a little weight when considering Worthy status, but its ascent must also be rewarding. Galtymore and its neigbours reveal their best aspect for those approaching from the Glen of Aherlow, viewing the sculpted north face, where hanging corries contain glacial lakes. Galtymore summit raises its head above the satellites, attaining an altitude of 918m (3011ft) which is almost 100m taller than the next highest peak, Lyracappul at 825m, standing 4km away at the western end of the range.

The nomenclature can be confusing for the newcomer. Firstly, Galty is pronounced with a short ‘a’ as in the American for a girl. Galty and Galtee are interchangeable spellings, although modern parlance has generally settled on Galty for the mountain and Galtee for the range (mountainviews.ie bucks this trend). Galtee is also a type of cheese and a popular brand of bacon, so it’s well-known name in Ireland! Furthermore, the Galtee Ballroom was the most popular Irish Dancehall in London and in business for sixty years until 2008. Finally, there is the currently inactive Galtee More gold mine in Western Australia, discovered by an Irishman. Coincidentally, there has been talk of gold in the Irish Galtees, although surveys so far have not resulted in mining, much to the relief of the conservationists.

Galtymore translates as the big hill of the Galtees and was first recorded as such during the Cromwellian land surveys of 1654. Galtee itself may derive from forests, although prior to this, back in Medieval times, the range was referred to as the Hump Mountains. Humpy is a rather accurate description. It is also around that time (following the Norman invasions) that this landmark mountain chain became a natural topographic boundary between baronies and, for the past four hundred years, the summit ridge of Galtymore has marked the border between County Tipperary and Limerick. Bagging county high points is a popular pastime in Ireland and with Galtymore, the completist climbs one and gets one free.

The range runs for around thirty kilometres westwards from the historic town of Cahir, which is the starting point for a full high-level traverse of the main ridge known as the Galtee Challenge, with an annual self-navigated walk taking place each June, organised by the Galtee Walking Club. Such events by various clubs have been arranged on and off since the 1980’s.

Numerous shorter walks are available, such as the most easterly summit Temple Hill, a fine viewpoint crowned by a large Bronze Age barrow, which is a popular walk often climbed on its own. The excellent book ‘Irish Peaks’ by Mountaineering Ireland includes this ascent as one of the four chapters it devotes to the Galtees. The other major source of information for routes is the mountainviews.ie website.

As noted above the northerly aspect is the finest, that from the south presenting the mountains as peaty moorland. Nevertheless, it is from the south that most ascents are undertaken, this having the advantage of a higher starting point. The principal launching pads are the Black Road and King’s Yard, the latter being a farm with camping facilities and refreshments. King’s Yard is also the usual starting point for Lyracappul.

The Black Road is a track that was created for transporting peat cut from the hills. Turf is no longer extracted although this practice probably gave the path its name. Some suggest it derives from large numbers of people walking to mass. Half way up, north of Knockeenatoung summit, there is an inscribed memorial stone in the shape an aircraft tailfin, commemorating three local airmen who fatally crashed on the slopes of Greenane West (across the valley) in 1976. The tragedy directly led to the establishment of the South Eastern Mountain Rescue Association, an organisation with around fifty volunteers that receives over fifty call outs a year.

The southern flanks of the Galtees are dominated by a deep layer of peat. The high altitude and inland nature of this landscape has created particular conservational importance and is a designated Special Area of Conservation. Dry heath (not quite the most appropriate description!) covers nearly half of the site along with blanket bog, the latter generally confined to the main ridge and the intervening cols. The main land use is sheep farming, although overgrazing is causing an impact along with the practice of heath burning, designed to improve the land for livestock but, when excessive, reduces the ecological diversity and causes a loss of peat. The large number of individual landowners increases the difficulty of negotiations for the conservation body when attempting to reduce stock levels and regulate burning.

It is worth noting that, common to many Irish hills in private ownership, dogs are not permitted due to sheep worrying. However, before the sheep were here, cattle would have been a common sight on the hills during the summer months, through the practice of transhumance or booleying as it known in Ireland. This involved taking advantage of summer grazing on the hills whilst freeing up the valleys for other uses. Often the herders would be girls, who lived in stone dwellings known as booley houses. Many of these survive as ruins throughout the hills. Butter would have been made on site and sent down to the creameries at Mitchelstown. The practice endured for centuries before dying out in the late 1800’s. Irish topographical maps mark the existence of booley houses rather aptly with the symbol of a brown cow.

Northern Loop

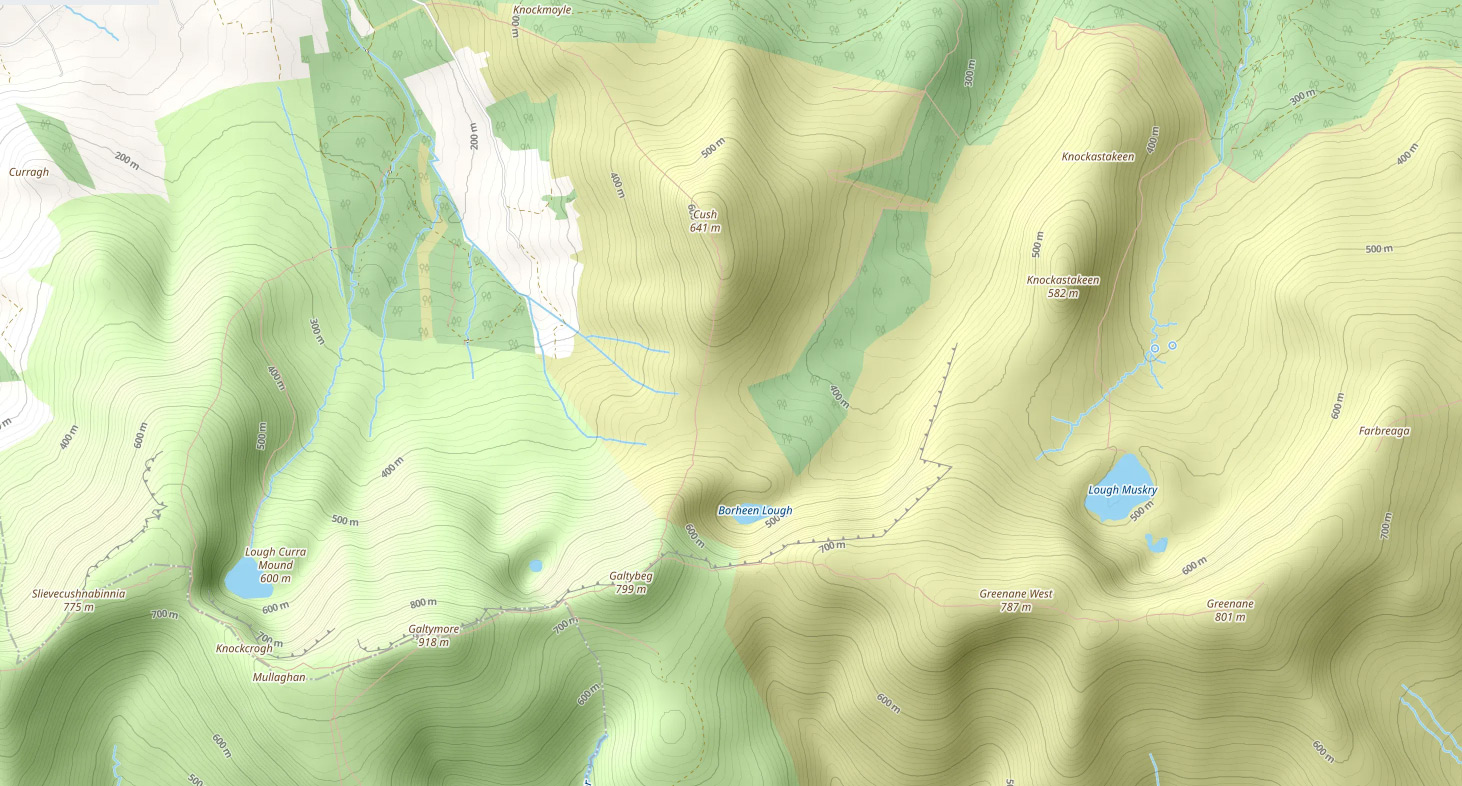

The northern profile of the Galtees is the most dramatic, featuring four lofty glacial corries carved by glaciers while the summits remained clear above the ice. Each corrie contains a deep lake with the most easterly corrie holding two, the small Lake Farbreaga being above Lough Muskry, which is the largest all the Galtee lakes. Muskry has been employed as a reservoir serving Tipperary for over a hundred years and also provides sport for brown trout fishermen. A circuit can be made from the north over Farbreaga (where there is a booley house) and Greenane, which boasts a fine rocky tor known as O’Loughnane’s Castle.

The major horseshoe walk of Galtymore commences from the car park south of Clydagh Bridge and provides the finest exploration of the Galtee Mountains. It has several names, including the Cushnabinnia or Clydagh Valley or simply the northern Galtee horseshoe (plus many more complicated ones), and covers around 15km with a sizeable 1200m of ascent. The Irish often call horseshoes ‘loops’ and this one can be walked in either direction, although both directions involve plenty of climbing! Clockwise is probably the steeper for ascents, which I normally favour, although with this walk I actually prefer to walk it anti-clockwise!

Taking the walk in an anticlockwise orbit, we begin by following woodland tracks, before turning right to emerge onto the open hillside with a green path marked by posts, on the initial slopes of Slievecushnabinnia. The posts drift off left towards Lough Curra along a gentle path, known as the Ice Road in the days when the lake provided the source for ice houses on the local estate. We continue straight on here up a steepish plod for around 300m until the angle eases.

The path handrails above the corrie to intercept a drystone wall, known as the Galtee Wall, built from the sandstone bedrock that defines these hills. Construction began in 1878 and took over thirty men around four years to build. It provided a boundary marker between the Massey-Dawson estates to the north and the Galtee Castle lands to the south, although principally its purpose was to provide employment at a time of economic hardship, in the vein of the earlier famine relief projects. The wall ran westwards from Galtymore west top for three and a half kilometres to Lyracappul.

We follow the wall to its end on the slopes climbing to the western summit of Galtymore. The top of the mountain is surprisingly extensive, with a cairn at either end plus other summit furniture erected amongst the wide scattering of conglomerate boulders, which are characterised by pebbles embedded in the sandstone.

There is a long damaged trig pillar close to the higher, eastern summit, although most attention becomes centred on the seven-foot, white painted steel cross erected in 1975 as the fourth in a series of structures standing here since 1933.

The view extends across the full breadth of Ireland, from the rolling Wicklow Mountains to the majestic Macgillycuddy Reeks.

The summit plateau of Galtymore is also known as Dawson’s Table after the major historical landowners on Tipperary side.

From here, the highest point, one might expect it to be downhill all the way, although for this horseshoe walk that is far from the case. The descent to the col below Galtybeg is fairly steep and eroded, however, it is the corrie that embraces Lough Diheen that arrests the attention.

There is much folklore surrounding this lake, concerning St. Patrick banishing a serpent to its depths, although some claim the location was Lough Muskry – this is the unreliable nature of folklore and why Mountain Worthies generally ignores it – however, for us, it is the extraordinary depth of the corrie and the trapped nature of the water that compels. The lake has no surface outflow.

A short climb leads to Galtybeg, which lacks altitude at just 799m, a failing of character made up for with the pleasing nature of its airy summit ridge. From here it is a fair drop of 350m (1150ft) to a boggy col, which for those taking the horseshoe in a clockwise direction is the most arduous section. Cush is even lower than Galtybeg, although the anti-clockwise walker it requires a stiff ascent from the col. The hill can be avoided by cutting down to the valley, but please don’t be tempted as it is well worth the effort.

Cush is an honourable final summit, low enough to show obeisance to the major mountain, yet individual in character to provide a major high point of the walk. The summit comprises a delightful ridge, offering glorious views to the heights scaled on this walk. Once again the descent is steep enough, if of no real concern, and leads neatly back to the starting point, completing a very satisfying circuit of Ireland’s heartland heights.

Worthy Rating: 70.5

Aesthetic – 22.5

Complexity – 13

Views – 15

Route Satisfaction – 13

Special Qualities – 7