Carrauntoohil – First Among Equals

In the south west of Ireland lies the ancient Kingdom of Kerry, boasting the magnificent mountain range of the Macgillycuddy’s Reeks, home to the country’s three highest mountains, its highest lake, and (arguably) Ireland’s finest ridge walk, the Cumeenloughra Horseshoe.

Crowning the range is Carrauntoohil, the roof of Ireland, which thus attracts more visitors than the other peaks of the ‘Reeks’, its ascent being principally achieved by a ‘tourist route’, the Devil’s Ladder, a path that is nevertheless rarely recommended by dedicated hillwalkers. So why should Carrauntoohil still warrant the accolade of being one of Ireland’s finest mountains? Read on…

The summit of Carrauntoohil reaches 1039m (3407ft) and along with its close neighbours, Beenkeragh at 1008m (3308ft) and Caher (1000m, 3281ft), comprise the only one thousand metre mountains in Ireland. In the world of Worthies, merely being the highest matters little for our purposes, except for perhaps adding an additional point for increasing the overall challenge of climbing them. What is far more crucial is that these hills are individually impressive, yet inextricably linked within a swashbuckling massif that captures attention from every vantage point.

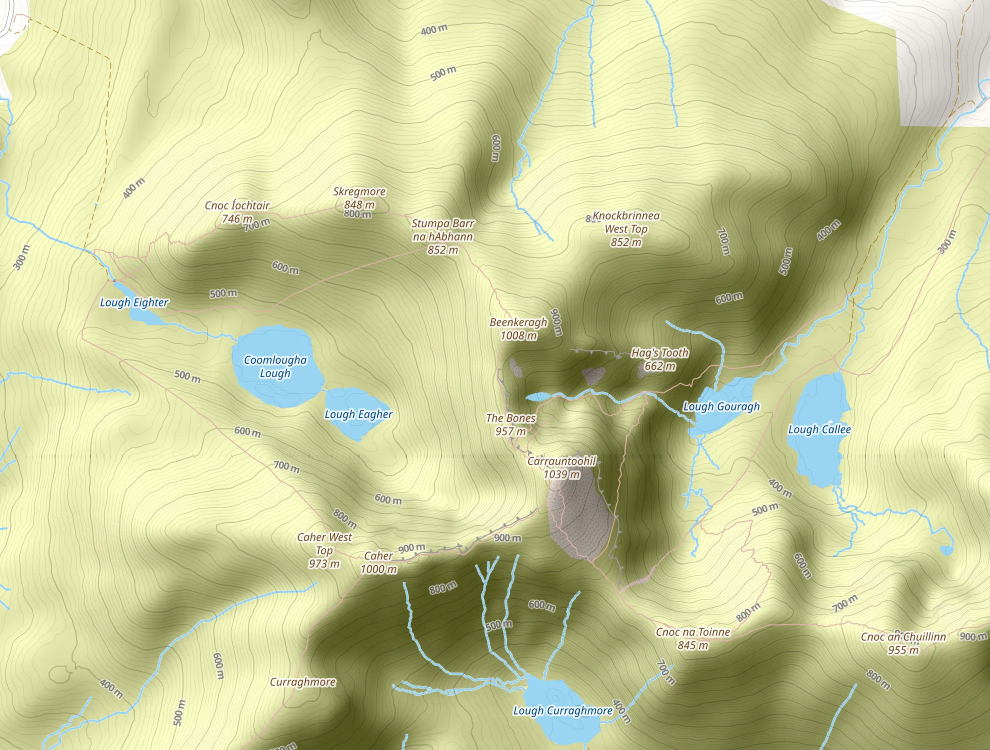

Map data below is courtesy of OpenStreetMap. To a view, a scaleable version follow this link: https://www.openstreetmap.org/?#map=14/51.99767/-9.74281&layers=P

There are two distinct massifs within the Macgillycuddy’s Reeks, our subject here being the western mountains. The eastern mountains are marginally lower although comparably rugged, further uplifted by the accolade of providing Ireland’s most renowned ridge traverse across the Big Gun. Whilst the two massifs are connected by high ground and part of an exhaustive long distance route, the ‘Reeks Ridge’, which includes all the principal summits in both, we consider west and east as separate Worthies.

The name Macgillycuddy’s Reeks derives from the local clan who were the major landowners in County Kerry. All this land has now been sold and the Reeks are in private hands, the largest share (mostly the eastern Reeks) being owned by part of the Liebherr Group (cranes) who have a major plant in Killarney. In Irish, the range is called Cruacha Dubha Mhic Giolla Mo Chuda, which translates as the black stacks of the McGillycuddy. It stretches from the Gap of Dunloe westwards to Lough Acoose and includes eleven of Ireland’s fourteen mountains above 3000 feet.

Black stacks these may be, although the underlying rock is Old Red Sandstone, massively eroded by glaciation into deep valleys thrusting rugged, exposed rocky slopes up to jagged ridges. Carrauntoohil merely happens to be the tallest of the range, whose most powerfully distinctive aspect is its north eastern face that broods over a deep corrie known as the Eagle’s Nest. Carrauntoohil is an anglicisation of Corran Tuathail, whose derivation is unclear, although there are a number of rather shaky suggestions that instil trepidation, such as ‘serrated peak’ or even the ‘mountain of torture’. The name of the local old parish was Tuath and a Corran may be a sickle, perhaps referring to the sharp, curved summit profile.

The mountain drains into three valleys, each containing lakes. Ascents can be made from all directions, although rarely from the south. Most ‘how to climb Carrauntoohil’ type blogs generally suggest just three major routes. One is a direct ascent via Caher from the west (part of the Cumeenloughra Horseshoe) with the main two (Devil’s Ladder and Brother O’ Shea’s) beginning from the most popular parking area of Cronin’s Yard at the northern end of Hag’s Glen. Where originally there were only around ten car parking spaces here, accommodation has expanded to over two hundred, along with a camp site and café. Alternative parking is also available nearby at Lisleibane.

There are several other routes to the mountain that diverge off the very pleasant Hag’s Glen, which gained a fine new path in 2016 courtesy of the Macgillycuddy Reeks Mountain Access Forum, an organisation established to protect this sensitive environment. They work closely with the landowners, who are extremely generous in allowing access to what is private land. The pressure of visitor numbers is considerable, creating unsightly footpath scars and causing other distress for the owners. For example, the mountains are employed extensively for sheep grazing and the prevalence of escalating sheep worrying led to a request that dogs were kept on leads. Sadly, an inconsiderate faction ignored this and a complete ban on dogs was imposed in 2013.

The most popular route is the Devil’s Ladder which, following a lengthy, gentle approach, scales an appalling scree gully that receives no plaudits, nor does the subsequent one thousand foot ascent to the summit. There are plans to improve the path although funding is a stumbling block, along with providing indemnity for the landowners, however, the Irish Government’s initiative MAP (Mountain Access Project) successfully arranged public liability insurance in 2021. Branching off before the lakes, a more compelling route takes the path that climbs steeply in three distinct ‘levels’ to and above Cumeenoughter Lake, regarded as the highest in Ireland at 2360ft (720m). It has become a prized wild swimming spot, due to its altitude and atmosphere, cradled in the Eagle’s Nest beneath the precipitous slopes of the north east face. The final climb above the lake is again an exercise in scree negotiation up Brother O’Shea’s Gully, before the col at the end of the Beenkeragh ridge is attained. The path is well seen in the featured image at the top of the page. This route is far less frequented than the Devil’s Ladder and offers an intimate involvement with the majestic Eagle’s Nest.

There is reasonably direct another alternative to Brother O’ Shea’s. From the first ‘level’ above Lough Gouragh, a path heads off left across the stream, passes a turf-roofed emergency shelter and proceeds through the splendidly titled Heavenly Gates, an obvious gap above. It then traverses more gently to arrive on the ridge above the Devil’s Ladder. This is a much less frequented, esoteric path, but does still entail the final climb to the summit in common with the main pack. Even quieter and reserved for scramblers, diverging from the same point, the rear of the jutting fang of the Hag’s Tooth can be reached and the ridge above ascended to Beenkeragh. Not finished with Hag’s Glen yet, two further alternatives leave the Devil’s Ladder path lower down, the first climbing The Bone ridge to the summit of Maolin Bui, followed by a long walk over the successive tops, or further up the glen at the foot of the ladder, the Zig Zag path leads to Cnoc na Toine.

Cumeenloughra Horseshoe

The valley leading west from Carrauntoohil exhibits three lakes and it is the circuit of the ridges that embrace this glen that comprise the Cumeenloughra Horseshoe, a hugely satisfying ascent of the three main peaks of the western Reeks. This may be regarded as the finest horseshoe in Ireland, yet the car park at Breanlee (top left on the map above) is far smaller (around twenty-five cars) than at Cronin’s Yard. This is a testament to the vainglory of summiting for the majority, rather than the virtues of the route.

The horseshoe can be accomplished in either direction, although here will be described as a clockwise circuit. Leaving the car park, altitude is speedily gained on the ugly concrete hydro road, which is atrociously steep to begin with but serves as an excellent warm up. You may consider it hard work, however, it feels rather more punishing in descent at the end of the day! The hydro road was formerly utilised as a paragliding launching point (I wouldn’t fancy running down it), although this practice was banned by the landowners since 2015. After a few hundred feet the track swings right, becomes grassy and takes a gently rising line to Loch Eighter.

Lough Eighter is the lowest of three lakes in the glen, the waters feeding pipelines that supply both drinking water and a small amount of hydro electricity. We cross the dam and follow the path onto the steep slopes of Cnoc Ioctair (lower hill). The path becomes less clear in places but picking your way up the acclivitous slopes is straightforward, if arduous. The angle begins to ease after a climb of around 750ft! The path remains sketchy at times over the subsequent mounting heights of Skregmore (large rough hill or similar) and Stumpa, although navigation is indubitable amidst clear conditions. Down in the glen, the central and largest lake, Cumeenloughra is frequently merged with the upper lake, Eagher, except during dry spells. Above the lake, the long descending ridge from Caher West Top awaits your closer inspection at the end of the day. As further entertainment, attempt to discern a large face on the hillside above the centre of the Cumeenloughra lake. I thought it resembled a monkey. Google Maps actually marks it as an attraction!

Rockiness only increases with altitude, the final pull to the summit of Beenkeragh is like climbing through a massive jumble of avalanched boulders. And what a place it is when you arrive at the second highest point in Ireland with a magnificent prospect in every direction. For those of a nervous disposition much of this may be neglected once their eye has settled on the intimidating prospect of the Beenkeragh Ridge connecting to Carrauntoohil. This is an impressive arete, although not half as formidable as it appears. Paths on either side come and go and rarely is there any necessity to follow the precise crest. The sense of exposure is not overly alarming either and in places you may well encounter sheep who have made their agile way to isolated grassy patches. The translation of Beenkeragh is Peak of the Sheep, so this should come as no surprise.

Taking the ridge in this direction the overwhelming focus is on the grandeur of the Eagle’s Nest corrie. Towards the terminus of the arete is the high point, aptly titled The Bones, not to be confused with the The Bone, the ridge directly east across Hag’s Glen. This final section perhaps requires the most thoughtful navigation, where the path drops obviously down to the left (east). You can scramble a long way down before traversing across or cut back at several points higher up, to enjoy the exhilaration of the position for a little longer.

Soon the col is reached at the top of Brother O’Shea’s Gully and a variety of paths through rocks and scree lead to the summit of Carrauntoohil. If you have been alone up until now, this is unlikely to continue. The top is marked by a darkly sombre sixteen-foot steel cross, erected in 1977 to replace a wooden cross first placed in 1952. The metal cross was manufactured by Liebherr for the local community and carried up in sections by a large team of volunteers. Originally it was painted white. Sadly the cross was felled by anti-Catholic protesters wielding an angle grinder in 2014 but re-erected a week later by a group of thirty local landowners and walkers who lifted and welded the cross back onto the remaining stump.

Caher (above) looks imposing as our third one thousand metre peak of the day, the connecting ridge is reached by initially retracing steps to a large cairn and then diverging half left. This is easy in clear weather, otherwise a bearing will be required. The ridge appears potentially hair-raising from a distance, but is tackled just to the left of the crest and, whilst pleasingly airy in places, it is wholly without difficulty.

There is the minor but grand peak of Caher West Top to stroll over before the descent proper commences with a steep bouldery slope which, as it gradually eases, becomes boggy in places. It feels like a long way at the close of the day, although there are so many ebullient memories of the walk to recall that you’ll soon be down to the hydro road… only to remember the soberingly steep bit at the bottom!

Worthy Rating: 85

Aesthetic – 27

Complexity – 16

Views – 17

Route Satisfaction – 16

Special Qualities – 9