Hungry Hill: Hungering for adventure

Hungry Hill exerts an enticing, powerful presence, undeterred by its relatively modest altitude. Irish mountains excel at compressing extensively gruelling terrain into compact proportions and Hungry Hill is a champion in this regard, warranting respectful exploration from its assailants. This is rocky country par excellence.

The mountain is, nonetheless, at 2247ft (685m), the highest point of the Beara Peninsula, whose extraordinarily rugged spine is defined by the Caha Mountains. Caha derives from ceatha meaning shower, and there are certainly plenty of those. As the Irish say, they don’t have a climate, just weather.

There is actually an Irish folk tale called The Bold Heroes of Hungry Hill, a story of a boy who sets out to “push his fortune ’till the harvest came in”. He is joined on his journey by various animals and they successfully tackle a band of robbers, returning stolen gold to its owner, who in gratitude gives the boy a living. On setting out for Hungry Hill, you are unlikely to encounter outlaws, although you will struggle with intractable country and feel like a bold hero if you successfully negotiate your passage!

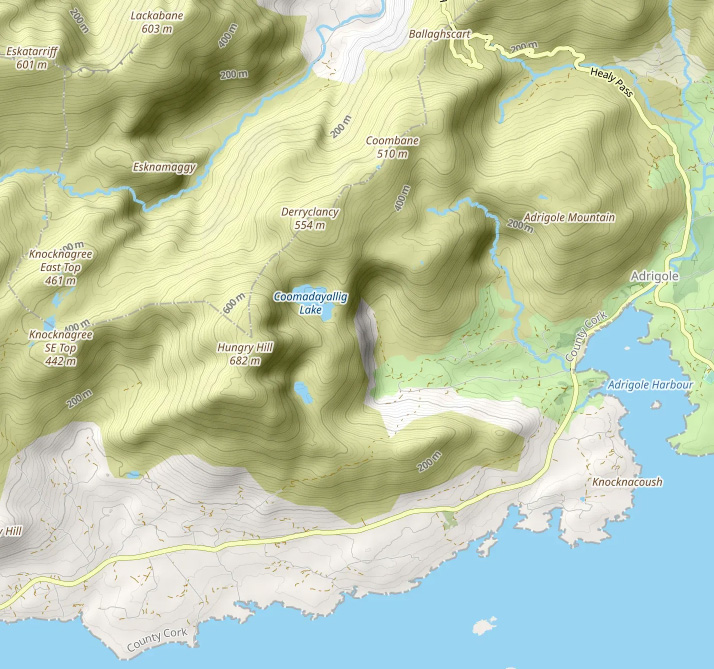

Map data above is courtesy of OpenStreetMap. To view a scaleable version follow this link: https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=13/51.69384/-9.78144&layers=P

The mountains are composed of Old Red Sandstone, revealing itself in a fashion peculiar to the Beara, forming angled bands of rock locally known as ‘benches’. These are separated by soft, peaty shelves, which together create a uniquely awkward terrain. Zig zagging is frequently required, adding distance and zapping energy. Paths are not as well-defined as might be expected on what ought to be a very popular mountain. However, the Irish population of hillwalkers is not large and visitors from further afield are generally attracted to the most famous peaks, so Hungry Hill is unjustly overlooked.

By now an appreciation of the arduous passage through these mountains has been instilled, although overcoming this toil is part of the attraction for some and undoubtedly adds a few points to the aesthetic and special qualities of Hungry Hill. What contributes the majority is the total immersion in such a rugged landscape, whose sense of remoteness far outweighs its physical isolation. To the newcomer, an atmosphere of foreboding lays heavy in the corries; an apprehension accompanies their progress through the unknown; a fear of straying into unseen dangers amidst the benches pervades any descent. And yet, if we follow the prudent advice of Edward Whymper and look well to each step, it is all perfectly manageable, perfectly safe, perfectly thrilling and perfectly magnificent.

Hungry Hill can feasibly be climbed from all directions, although there are few clear sections of path, therefore sound navigational judgement is required and, most importantly, walking in mist increases the challenges and the dangers of potentially treacherous territory.

The approach from the Healy Pass is one of the most frequented, being a relatively straightforward out and back along the broad ridge over Coombane and Derryclancey. This route benefits from a start at close to 1,000ft above sea level and the drive over the pass to reach the starting point is one of the finest scenic roads in Ireland, the route originally created as a famine relief project in 1847.

The stupendous east face rises in two formidable rocky walls separated by a shelf that cradles two lakes; a scene well depicted in the featured image at the top of the page. The face is approached by the Coomgira Horseshoe, which starts and terminates at the two road ends in the valley leading in from Adrigole, although the link between the two roads is private land. The horseshoe climbs up the stream to the left of Coomarkane Lake, ascends Hungry Hill by negotiating the ‘benches’ of the southeast ridge, then crosses to Derryclancey before making a descent to Derreen.

From the north, at the end of the Glanmore Valley, the river can be followed into The Pocket and up to Knocknagree, then turn east via Glas Loughs. Combined with the Healy Pass route, this makes a horseshoe walk. Direct ascents from Glanmore to Hungry Hill or Derryclancey are difficult.

Ascents from the west and south usually commence from Rossmackowen Bridge, although the odd parking space exists higher up, closer to the Beara Way footpath which cuts across the south flank of the hill. When researching this feature, choosing a route that would incorporate all the finest aspects of Hungry Hill resulted in the following suggested circular walk taking in the southwestern ridge and the eastern lake corries.

The southwestern ridge is a striking sight, thrusting a bony arm skywards as a bold invitation to the adventurer. It can be gained at several points, although it is most pleasing to follow the ridge in its entirety. To gain entry, take the main track beyond Park Lough around the base of the ridge, then cut back onto it. The initial track itself is known as a bog road, such routes being utilised to access areas of turf cutting, although few gather peat in modern times. This particular section is followed by the Beara Way, a long distance footpath taking a mostly inland circumnavigation of the peninsula. If the southwest ridge appears too intimidating, Hungry Hill can be climbed from the lonely amphitheatre beyond the foot of the ridge, either by following the steam to the col or tackling the slopes on the right, leading back to the top of the ridge.

Ascending the ridge feels like climbing a monumental stone ladder, whose rungs form the exposed ribcage of the mountain. In all honesty there need be no difficulties, any major rock steps can generally be bypassed to the left. Nevertheless, it’s a tiring process!

And suddenly, the rugged slopes abate, the angle eases, and everything changes to an unexpected expanse of boggy moorland. Even a path begins to materialise as you trend right to the south summit. The southeast ridge joins here and it’s a spectacular viewpoint looking out to sea. Perhaps it is due to this prominence that a substantial round cairn was built, visible to mariners in Bantry Bay. However, this is not the highest point of the mountain, that being the north summit, a ten-minute stroll across a damp saddle.

Just before the north summit a conspicuous white cairn is passed. It claims no high point, although clearly was constructed with dedication, for its jumble of quartzite rocks required collection from far and wide. The builder was a local Doctor, John Lyne from Castletownbere, who made 1300 ascents of Hungry Hill during his lifetime (and also climbed Carrauntoohil 205 times).

There is no disputing the lure of the name Hungry Hill, having been bestowed upon an Irish neighbourhood in Springfield, Massachusetts and adopted by Daphne Du Maurier for her novel about a copper mining family, which is set on the Beara although some twenty miles to the west near Allihies. The etymology, however, is vague. In Irish the hill is called Cnoc Daod which may mean hill of the tooth or jaw, but also the hill of envy, and from this some propose that seven of the Beara hills were named by a local priest after the seven sins. The English version, Hungry Hill, has been in use since at least 1655, yet no one knows whence it came, although local speculation suggests a corruption from Angry Hill.

The southwestern ridge may have constituted sufficient adventure for some, although there is much more to come on this circuit. To begin the descent there is a helpful track and a few cairns, which fade all too soon into an intermittent path that only keen eyes will spot. The key is not to follow the temptingly fine ridge top but to drop diagonally down to the left keeping below most of the rocky outcrops, onto a grassy shelf in the lower section. Meeting a stream, we descend into a boggy hollow which is followed rightwards, basically in a level arc, before dropping down to the eastern end of Coomadayallig Lake. It does look possible from below to have taken a more direct line from the boggy hollow to the lake, although I haven’t tested it!

Coomadayallig is the larger of the two lakes, Coomarkane being to the south, and because the names are a bit of of a mouthful they are often simply referred to as the north and south lakes. Both lakes lie in deep hollows beneath the broken yet majestic crags that protect the summit from direct attack, although weaknesses can be exploited by the brave. At the lakes we are standing upon that shelf seen from Adrigole, perched halfway up the mountain. Each lake discharges a stream; that from the south can be followed but the northern outflow soon evolves into a seven-hundred-foot high cascade known as the Falls of Adrigole or The Mare’s Tail, being the tallest waterfall in Britain and Ireland. That’s quite an accolade. Unfortunately the falls occupy private land and there is no public access. They can be seen well from below, although not from our location above.

The terrain is mostly pathless and you are likely to be alone in this rugged wilderness, heightening the sense of remoteness, despite the relative proximity to civilisation. Reaching the south lake involves a gentle, grassy incline to the dividing rib, followed by a longer, equally amenable descent, yielding an approach to a much smaller stretch of water, once again embosomed by towering crags which rise directly to the summit of Hungry Hill. Crossing the outflow, another gradual, slightly rightward trending ascent is required to skirt the lower reaches of the southeastern ridge. Attempting to stay low or too far to the left will only make the journey longer.

Once around the ridge the aim is to take a diagonal line, not losing height too quickly, eventually meeting the Beara Way footpath for the final mile back to Park Lough. If you accomplish this without too many diversions around obstacles and with relatively dry boots, then congratulations will be in order for your impeccable route finding prowess!

Worthy Rating: 79

Aesthetic – 24

Complexity – 16

Views – 17

Route Satisfaction – 14

Special Qualities – 8